Wed, 26 Nov 2003

Rocket Fuel

My boss is fond of saying, “It isn’t rocket fuel.” Well, this is rocket fuel.

When I was 13 or 14 years old, my brother and I enjoyed building and launching model rockets. My father, the scientist, made rocket fuel for us. I remember him mixing the ingredients in a large pan on the stove.

“Listen,” he said. “This is dangerous. If I tell you to run, then you run. Run out into the orchard and don’t come back to the house until I call you. Understand?”

We nodded and watched. Not long afterwards, Dad became very excited and shouted, “Run! Run!”

Tue, 11 Nov 2003

Vernier scale

I've been going through some of the instruments and gadgets that belonged to my father. A common feature on many instruments is a vernier scale.

I can remember Dad teaching me how to read a vernier scale, but I never gave much thought, until now, to how and why it works.

The vernier scale is based on some very simple mathematics that yields a surprisingly powerful and useful result.

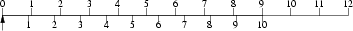

Consider the following scale. The base scale is on top, the verier scale on the bottom.

Notice that the vernier scale divides 9 units on the base scale into 10 equal parts. Therefore, each vernier unit is 0.9 base units.

1

on the vernier scale falls on a point that must be 0.9 on the base

scale, even though the base scale is not marked at that point. If we

slide the vernier scale 0.1 base units to the right, the 1

on both

scales will align precisely, and the arrow at the origin of the vernier

scale will be positioned precisely at 0.1 base units.

If we slide the vernier scale to the right until the 2

marks on both

scales align, the arrow on the vernier scale will be positioned at 0.2

base units. It must be, because each vernier unit is 0.9 base units; 2

vernier units equal 1.8 base units; 2 – 1.8 = 0.2.

So, as we can see, when a mark on the vernier scale aligns with a mark on the base scale, that mark on the vernier scale indicates, in tenths, where the vernier arrow falls on the base scale.

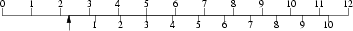

Take the following setting, for example.

The 3

on the vernier scale aligns with a mark on the base scale, so

the arrow falls at 2.3 on the base scale.

A common set of vernier calipers allows measurements in thousands of an inch. The base scale is marked inches, and tenths, with each tenth divided into 4 parts (0.025 inches). The vernier scale divides 24 of the smallest marked units on the base scale into 25 vernier units. Each unit on the vernier scale is, therefore 0.024 inches long, 0.001 inches shorter than a unit on the base scale. When a measurement is taken, the thousandths indicated on the vernier scale are added to the nearest 0.025 inch mark on the base scale, left of the vernier origin.

It would be impractical to mark a rule with thousandths of an inch and even more impractical to use, but by employing a vernier scale, measuring that accurately is simple.

Fri, 20 Jun 2003

Summer Solstice

There was some discussion at work today, on a break, about the Summer Solstice. Tomorrow is the longest day of the year in our neck of the woods.

I thought I had a reasonably good understanding of the earth’s tilted axis and it’s effects on the Sun’s path through the sky from my observation point here at 47.63 degrees north latitude. But someone asked, “Is it the longest day of the year everywhere in the Northern Hemisphere, or just everywhere north of the Tropic of Cancer? And, if it’s the longest day of the year at some dividing line, how can it be the shortest day of the year just on the other side of that line?”

It wasn’t until I got home and found a few quiet minutes to close my eyes and ponder the question that it all made sense.

Yes. Tomorrow is the longest day of the year everywhere in the Northern Hemisphere, and conversely, the shortest day of the year everywhere in the Southern Hemisphere. And you can stand on the dividing line between the two.

Right on the equator, every day, year-round, is the same length. Twelve hours of light and twelve hours of darkness. A few feet north, the days get just a little (as in infinitesimal fractions of a second) longer as the North Pole tilts toward the Sun, peaking at the Summer Solstice. The farther from the equator you get, the more pronounced the effect, until, at the North Pole, the Sun does not rise, or set. It circles sky, the 23 degrees above the horizon.

At the equator, although the Sun makes a northward arc as it travels across the sky, it rises due east and sets due west. At our latitude, this time of year, the Sun rises is the northeast and sets in the northwest, arcing southward as it travels across the sky. It’s the extra time it spends morning and evening, north of us, that gives us the extra hours of daylight.

Now that I’ve resolved my own confusion over the matter, I should be able to get a few hours sleep before the long day begins …unless I start worrying about when North, South, East, and West should be capitalized and when they shouldn’t.

About this weblog

This site is the personal weblog of Marc Mims. You can contact Marc

by sending e-mail to:

[email protected].

Marc writes here about cycling, programming, Linux, and other items of personal interest.

This site is syndicated with RSS.

Archives

Credits

CSS stolen from Tom Coates who didn't even complain.